Student Banking Package

A banking package to help you through your final two years of study

This banking package includes an everyday bank account with an optional overdraft facility and a Platinum credit card packed with rewards and benefits.

Learn More

My time spent in the neurosurgery department at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH) in Kathmandu, Nepal was eye-opening, challenging and potentially career-path altering. Overall, I loved the experience and wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it to any student interested in travelling to Nepal for their clinical elective.

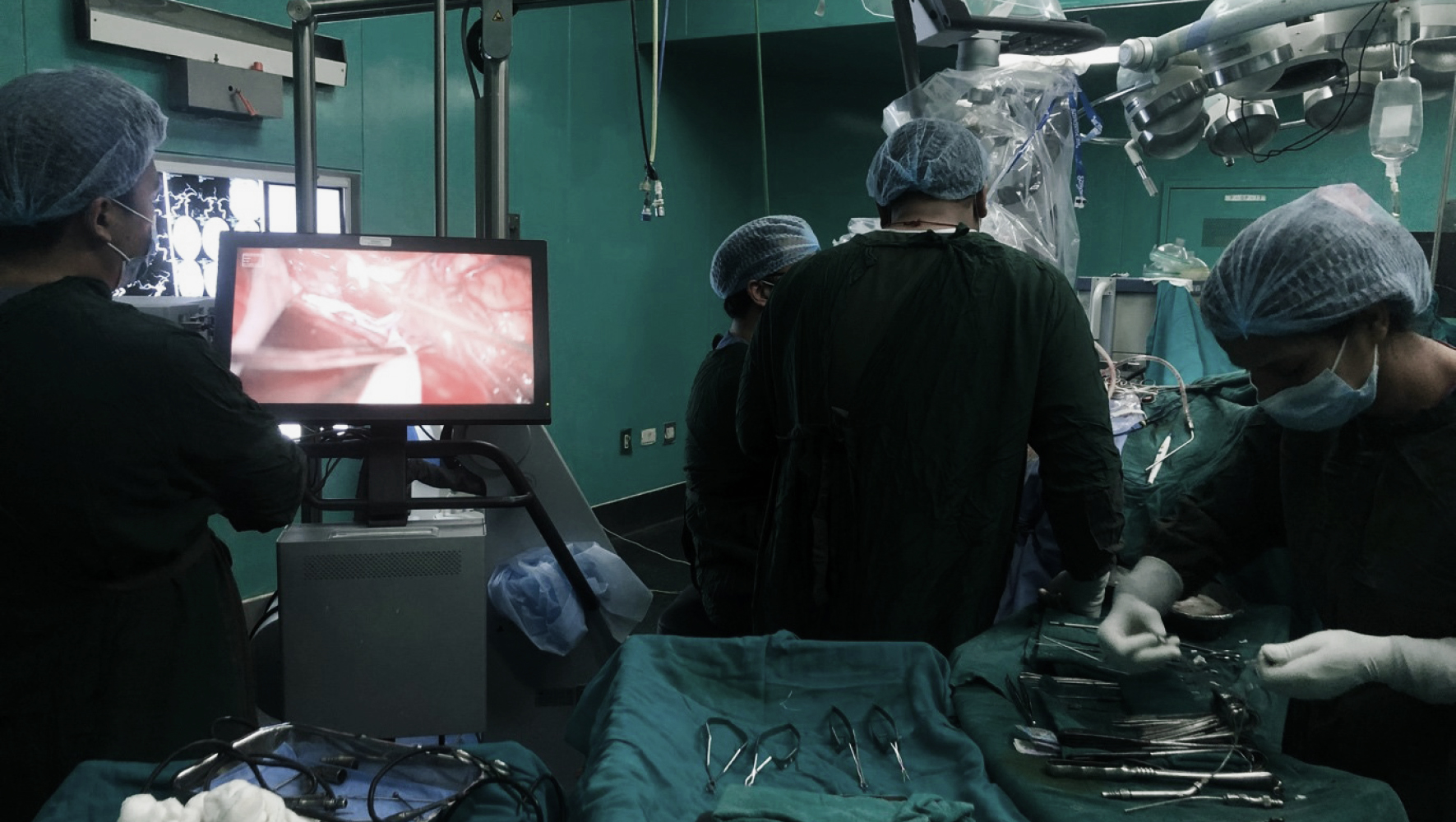

My time spent in the neurosurgery department at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH) in Kathmandu, Nepal was eye-opening, challenging and potentially career-path altering. Overall, I loved the experience and wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it to any student interested in travelling to Nepal for their clinical elective. After the meeting, around 9.15am, morning rounds started. Visiting patients on the ward, in high-acuity beds, in the peri-operative short-stay-unit and then the ICU became a routine. Ward rounds would usually finish around 11.00am, after which we could change into theatre attire ‘scrubs’ and head to the operating room.

After the meeting, around 9.15am, morning rounds started. Visiting patients on the ward, in high-acuity beds, in the peri-operative short-stay-unit and then the ICU became a routine. Ward rounds would usually finish around 11.00am, after which we could change into theatre attire ‘scrubs’ and head to the operating room.

Activities around Kathmandu

Activities around Kathmandu